We use cookies to provide you with the best possible service and a user-friendly website.

Please find our Privacy Policy on data protection and data management here

Please find more information on the cookies here

Wonders of the waxen realm – on the ancient uses of honey and beeswax

Now that the first flowers of spring have withered, bees are again hard at work gathering pollen – just as they were thousands of years ago. Ancient Greek and Roman authors were keenly interested in these busy, aerial insects. Some of their theories may seem strange today: some thought that the reproduction of bees was unusual in that they gathered their offspring from flowers, others assumed their leader – the queen – to be male. They were, however, right in recognising that bees, like people, lived in state-like organized communities, and were amazed both by their skills in building hives and by their exemplary diligence.

But bees were perhaps most admired for having been “created for the benefit of man”. Beekeeping was an important part of Greek and Roman agriculture: bees not only pollinated domesticated plants but also produced honey and beeswax, which were used for a surprising variety of purposes in antiquity. Let us see a few examples by taking a look at artefacts from the Collection of Classical Antiquities!

Stations

- Sweet delicacies

- Gift to the gods

- In the realm of Hades

- Honey as a preservative

- Surface treatment with wax

- Wax and bronze

- Hollow wax casting

- Reusable “notebooks”

- Painted portraits from Egypt

Sweet delicacies

Honey was primarily consumed as foodstuff. According to a myth, bees – or, in another version, a princess called Melissa (“the bee”) fed honey to the new-born Zeus. In antiquity, honey was the most important sweetener, and was used to flavour cakes.

This South Italian terracotta statuette depicts the pot-bellied Silenus, who belonged to the retinue of the god Dionysus. He holds a basket in his left hand, laden with round and pyramid-shaped objects – probably cakes. Although only traces of this survive today, the entire statuette was originally painted, which may have helped in the interpretation of small details.

Silenus with goat and basket

Tarentum, 3rd–2nd centuries BC

Gift to the gods

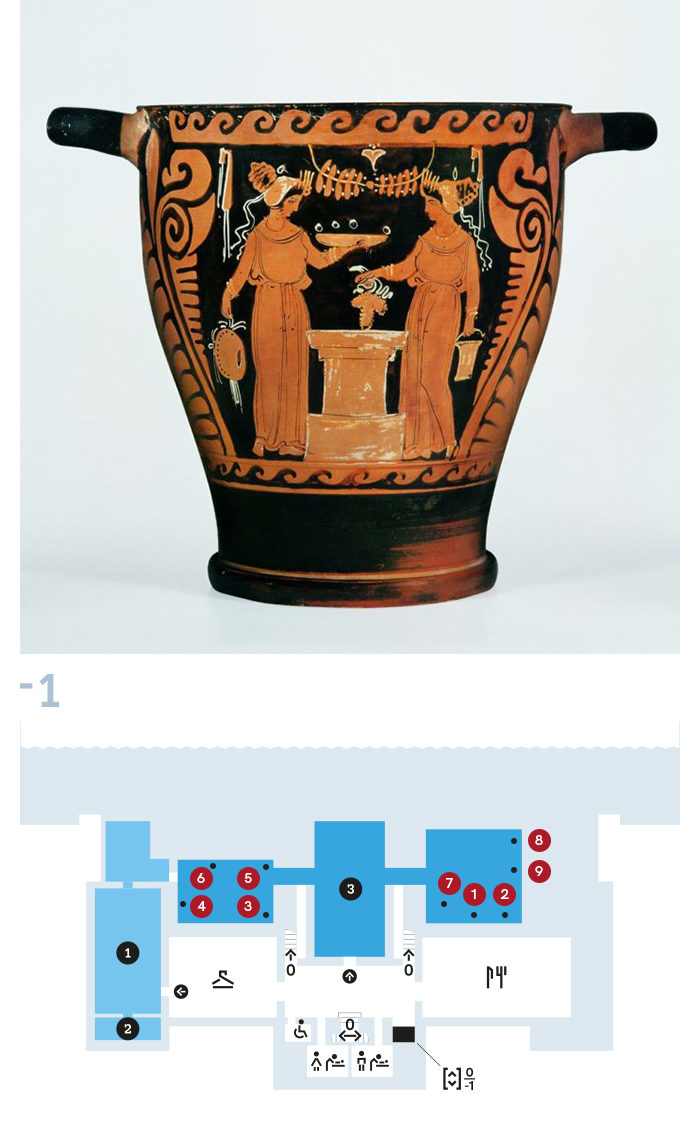

Honey and baked goods were given to the gods as votive offerings – perhaps the cakes in the basket of Silenus were also meant as such, similarly to the goat that he is leading behind him. The vase here depicts an offering scene. The woman on the left presents a bowl full of round cakes or fruit, while her companion holds a bunch of grapes above the altar. There is a round hand drum, a tympanum in the hand of the former figure, while the latter holds a vessel for offering.

Red-figure skyphos: women offering at an altar

Campania, 325–280 BC

In the realm of Hades

Honey was also part of the funerary offerings, and it was customary to present the deceased with honey cakes. Mythical stories relate that such goodies were also used to appease Cerberus, the three-headed dog guarding the entrance of the Underworld. This bronze tablet from the Roman Imperial Period shows the beast seated at the foot of a bearded god, who is not, however, his usual master, Hades (or the Roman Pluto): the hammer, key and caduceus in his hands are not the typical attributes of the lord of the Underworld. The relief depicts deities of a culture that used the motifs of classical Graeco-Roman art but transferred them into a new context.

Votive tablet: two deities in an aedicula

From Herkulesfürdő, 2nd–3rd centuries AD

Honey as a preservative

Honey was also part of the funerary offerings, and it was customary to present the deceased with honey cakes. Mythical stories relate that such goodies were also used to appease Cerberus, the three-headed dog guarding the entrance of the Underworld. This bronze tablet from the Roman Imperial Period shows the beast seated at the foot of a bearded god, who is not, however, his usual master, Hades (or the Roman Pluto): the hammer, key and caduceus in his hands are not the typical attributes of the lord of the Underworld. The relief depicts deities of a culture that used the motifs of classical Graeco-Roman art but transferred them into a new context.

Votive tablet: two deities in an aedicula

From Herkulesfürdő, 2nd–3rd centuries AD

Surface treatment with wax

Beeswax, which the bees employ for building honeycombs in their hives, can also be utilized in a variety of ways. The Greeks and Romans often used it for coating, for example, to preserve ripe apples. They also treated marble statues and painted walls with a mixture of so-called Punic wax and oil to protect their surfaces and colours from environmental effects. The water-repellent property of wax also made it suitable for insulating the inner walls of pottery: this is suggested for example by traces of wax on some of the storage vessels that survive from the Bronze Age. These pithoi, which lined the storerooms of Cretan palaces, and sometimes had capacities as large as several hundred litres, mostly contained oil, grain and wine.

Fragment of a storage vessel with decoration in relief

Crete, Knossos, 1600–1190 BC

Wax and bronze

Another advantageous quality of wax is its ability to soften and become pliable when exposed to even a little bit of heat. It melts and liquefies at a relatively low temperature. Ancient metalworkers employed these characteristics during the so-called lost wax process. The simplest version of the process was used to create solid bronze objects: this is how the nude male figure in the picture – one of the earliest bronze statues from ancient Italy – was made. First, the statuette was modelled in wax, then surrounded with clay. When heated, the wax melted and ran out from the clay mould, which was in turn baked hard. The hollow space left behind by the wax was filled with molten bronze, then the clay mould was broken away from the statuette. The uneven surface of the statuette evokes the surface of the wax model. Some details – the hair, the eyes, and the nipples – were added after the statue was cast.

Bronze statue of a man

Latium, 850–800 BC

Hollow wax casting

It would have been both costly and risky to create solid bronze statues in larger sizes. The problem was solved by another method of the lost wax process: hollow wax casting. In this method, the wax model was formed around an inner clay core, which was fastened to the outer clay shell by metal pins. This ensured that the core remained stable when the wax was melted from the mould. The bronze statue, which was cast between the two layers of clay, thus became hollow. The griffin’s head from the Collection of Classical Antiquities was created with this technique. Such griffin-heads decorated the rims of large bronze cauldrons, which were popular votive gifts in the so-called Orientalising period (700–600 BC) both in the Greek mainland and in Italy.

Griffin-head from a bronze cauldron

Samos (?), 700–680 BC

Reusable “notebooks”

The malleable surface of beeswax was perfectly suitable for incising letters. Archaeological evidence shows that foldable tablets that had their inner faces coated with wax were already used for writing in the Bronze Age. The Greeks and Romans also had such two-and multi-leaf writing tablets or “notebooks” for jotting down short texts, messages and school exercises. They wrote with a sharp writing tool (stylus), the other flat end of which was used as an eraser to wipe away the text. They could even hide secret messages written on the wooden board under the wax. On this Anatolian tombstone from the Roman Imperial Period, the writing tablet and the writing utensils flanking the central wreath testify that the deceased had been a learned man.

Tombstone of a man

Hermos Valley (Central Turkey), 159/160 AD

Painted portraits from Egypt

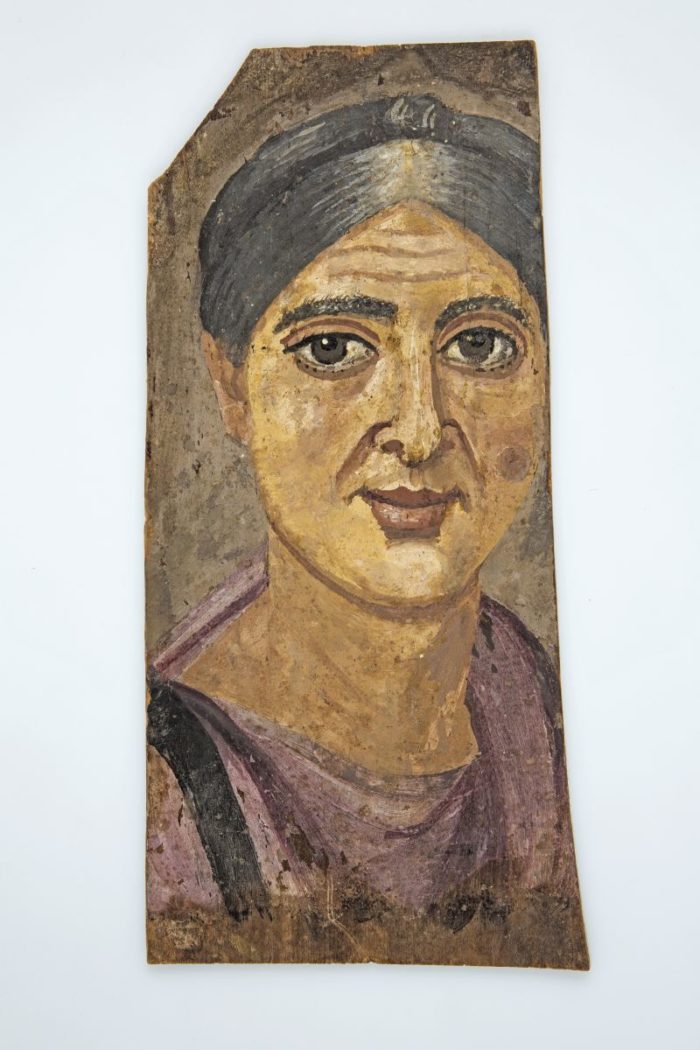

Beeswax was not only employed in the creation of bronze sculptures, but also in the so-called encaustic technique of painting. Pigment was added to heated beeswax, then the paint was applied to the wooden (more rarely ivory) panels with brushes and various metal tools. The bright colours of the “waxes” and subtle shading resulted in lifelike images, as in the case of Egyptian mummy portraits from the Roman Imperial Period. Following Egyptian customs, these portraits, which were painted on panels of wood or linen shrouds, were placed above the face of the deceased. The clothes and hairstyles of the depicted people, however, echoed Roman fashion – as is evident in the portrait of this lady. Similarly to late antique textiles, mummy portraits were preserved thanks to the dry climate of Egypt. They belong among the very few examples of ancient panel painting known to us today.

Mummy portrait painted on wood: elderly woman

Egypt, Philadelphia (Er Rubayat), after 120–130 AD