We use cookies to provide you with the best possible service and a user-friendly website.

Please find our Privacy Policy on data protection and data management here

Please find more information on the cookies here

The Followers of Leonardo

If we see several Madonna paintings by the better-known followers of Leonardo on the walls of the museum, we get the feeling that we are looking at a large group of twins with the same number of interchangeable, almost identical, lively little children. We may honour one of these with our careful attention, primarily out of respect for the enormous authority of the master who established the school, but it is enough if we just cast a quick glance in the direction of all the others. We become rapidly satiated with the flattering harmony and that self-promoting beauty that completely lack Leonardo’s essence of seeking the secrets of man and nature with an almost demonic restlessness.

Let this now be a unique experience in which we take five such paintings to look behind the superficial identity of followers of Leonardo and not merely repeat the generalities of “epigones” and “penny ante work”.

The compositions of Boltraffio, Bernardo Luini and Giampietrino attract our comparison with one common motif, the movements of the infant Jesus which are triggered in all three paintings by the basic instinct of curiosity.

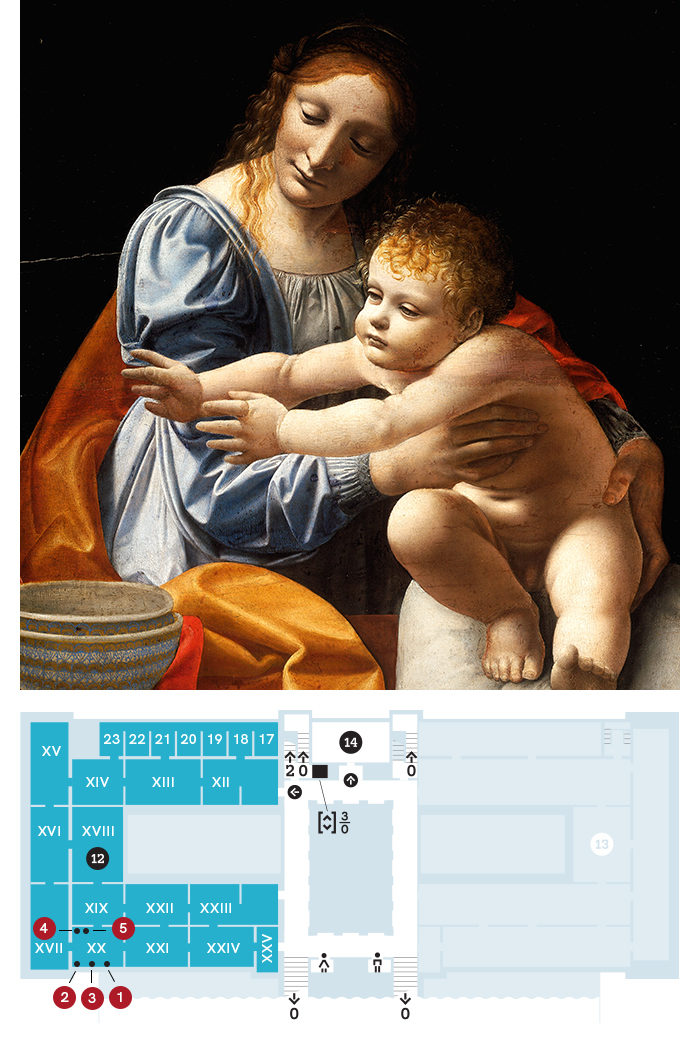

Stations

- Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio: Madonna and Child

- Bernardino Luini: Madonna and Child with Saint Catherine and Saint Barbara

- Giampietrino: Madonna and Child with Saint Jerome and Saint Michael

- Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci: Virgin and Child with St John the Baptist

- Martino Piazza da Lodi: Madonna and Child with infant Saint John

Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio: Madonna and Child

The Boltraffio is the earliest of the three paintings, created during the last decade of the 15th century. It does not take a great deal of study to realize that Boltraffio’s Madonna is the one most closely related to the art of Leonardo. This is so much the case that even today we may be willing to accept the supposition of Wilhelm Suida, one of the most outstanding Leonardo scholars, that parts of the Boltraffio Madonna were in fact painted by Boltraffio’s genius of a master. The delicately chiselled lines of the face, the shading which follows precisely the relief of the forms and the sensitive presentation of Mary’s tresses and Jesus’ curly locks come thought-provokingly close to Leonardo’s level. It would also be very difficult to find fault with the foreshortening of extended and bent legs or with the magnificent gathering of the folds of the sleeve, bathed in the silky sheen, suggestive of a profound study of nature. The composition is worthy of Leonardo as well. Successfully exploiting the motif of the broad parapet, the movements in all directions of the space are gathered together by pyramidal construction simply and without effort. In this way the principal innovation of the High Renaissance is realized, namely the richly and dynamically articulated pictorial unity and harmony arising from polyphony. The painting also has some less successful parts and for these it is undoubtedly the student, Boltraffio, who is responsible, whose numerous later works are characterized by unevenness in quality. Such detail include the thin arms of Jesus, the inaccurately foreshortened rim of the pot and the cloak which covers the parapet and refuses to assume a naturally vertical position.

We would be in error if we assumed that the followers of Leonardo, coming after Boltraffio, would understand more of the teachings of the Master or that the ideal of harmony of the High Renaissance would take shape in their works in the more complex and refined fashion. Albeit in different ways both Luini and Giampietrino’s work convince us of the opposite.

Bernardino Luini: Madonna and Child with Saint Catherine and Saint Barbara

In Luini’s paintings the method by which Catherine, Mary and Barbara are lined up side by side is a distinct step backward toward the quattrocento. Jesus is a lively child as is Boltraffio’s but his position is simpler and more respectful of the plain of the picture than in earlier painting. Luini’s tendency to simplify can be seen in all these details, but suffice it to say that we will find nothing here that even comes close to the masterful handling of the fabrics that we had admired in the Boltraffio painting or in the faces, particularly Mary’s where the design and sfumato shading are significantly weaker than in the strongly Leonardesque painting.

Luini’s is a painting technique that avoids problems, is smooth in nature and technically sound. In this instance, to avoid disturbing the monotony of awkward piety, he took the attributes of Catherine and Barbara; the wheel and the tower, and made them into modest decorative elements on the hems of their dresses.

Giampietrino: Madonna and Child with Saint Jerome and Saint Michael

Giampietrino would never have refrained from presenting the attributes of his saints with great emphasis. He made them into an intentionally comical side issue. Jerome’s lion shows off his sharp teeth and lolling tongue, Saint Michael’s satanic imp entertains the viewer with his ram’s horns, bat wings, wrinkled ears, thick lips and wide-open eyes. The Archangel himself is a sickly pale, vain gloriously smiling, androgynous looking being who holds his sword in front of himself without any bellicose intent and who is merely an extra in the scene played by Mary, Jesus, and Saint Jerome. The composition is much more agitated than Luini’s and the horizontal format, chosen in preference to the vertical one, assists in spreading out the undulations of the outlines and of the draperies. This is a conventional, artificially generated activity, vastly different from the Boltraffio Madonna’s natural mobility, radiating equally in all directions. So far as the details are concerned, with Luini we could speak of simplification, with Giampietrino we observe a trend to complicate things but starting from abstract formulae and not from reality. In the depiction of the hair and the beard there is clearly an approach to ornamentation and, if I may refer to Boltraffio’s handling of fabrics for the third time, it is miles apart from Giampietrino’s playful, back-and-forth folding of the dresses.

Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci: Virgin and Child with St John the Baptist

This painting from the estate of Count János Pálffy was languishing in the vaults for almost one hundred years and only after its restoration in 2007 was it included in the permanent exhibition. The identity of the artist who painted this work masterly evoking the style of Leonardo in some of its details remains unanswered to this day. What seems certain is that it was someone either working in Leonardo’s workshop or who had access to the master’s drawings. The painting is reminiscent of Leonardo’s famous works in many respects: the rocky formation in the background echoes the scenery of The Virgin of the Rocks, while Mary’s figure brings to mind a drawing by Leonardo now preserved in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

The Virgin kneeling in the foreground extends her arms protectively over the children. Before them are blooming flowers, behind them an idyllic hillocky landscape and in the background mountains looming in a bluish haze. However, a stark contrast can be perceived between the remarkably executed landscape background and the figures, which might be explained by the composition being unfinished.

Our gaze is primarily drawn to the richly detailed landscape elements. A few decades earlier, Italian artists were able to admire such motifs only in works by their Flemish contemporaries, and then they started to adopt these. There are many exquisite landscape details worthy of our attention; the botanic accuracy in the depiction of the flowers in the foreground suggests the influence of Leonardo’s analytical method on the painter of this composition.

Martino Piazza da Lodi: Madonna and Child with infant Saint John

In order to see how many-facetted Leonardism could be, let us examine one more painting from this circle, the Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John by Martino Piazza di Lodi, painted around 1515. However distant the compositional similarity, beyond the thematic kinship and the general Leonardesque character, the landscape in the background and the mysteriousness of the expressions, inevitably remind us that like so many other works in Lombardy during the first half of the 16th century, this painting could never have been created without the artist being thoroughly familiar with the Madonna of the Rocks. Compared to Leonardo, this master coming from Lodi near Milano, simplifies as much as Luini and Giampietrino but less routinely than they and with considerably more complex and refined artistic means. The peculiar angularity of the movements, the narrowing of the space to be filled by the figures, the iconic frontality of the Virgin sitting on the ground and holding her mantle protectively, the alabaster smoothness of the skin surface and the spider web fineness of the lights appearing on the red dress are in contrast with the Leonardesque ideal of liveliness but together they have a very strong effect and convince the viewer of the validity of the artist’s vision and of his originality. An important component of the peculiar mood generated by the characters is the magical forest visible on the right with its dense leafy branches and meticulously detailed, lacy light. There are few paintings where we can sense quite so clearly that the emotionally rich landscape art of Albrecht Altdorfer and other masters of the “Danube School” was not entirely without its effects even south of the Alps.