We use cookies to provide you with the best possible service and a user-friendly website.

Please find our Privacy Policy on data protection and data management here

Please find more information on the cookies here

Perspective

How do we perceive the world around us and how do we record it these days? Primarily in photographs but also on film, in HD or 4K… This was not always the case. Let’s travel five hundred or a thousand years back in time. How did artists see the world that surrounded them? And how did they depict it on a flat surface? What was more important for them? The exact representation of reality or the depiction of its essence? Conveying the hierarchy of divine order or recording the features of a face precisely? Examining these questions will take us closer to understanding why there are such significant differences between the depiction of the same element of reality (e.g., a landscape by a lake) in Egyptian, medieval, Renaissance, baroque and rococo art?

Stations

- Fragment of a coffin

- Lucanian red-figure nestoris

- Guido di Domenico di Tantuccio: Account book cover for the Biccherna office of the city of Siena (currently not on display)

- Maso di Banco: The Coronation of the Virgin

- Petrus Christus: Virgin and Child under an Arch

- Andrea del Verrocchio (workshop of) Biagio d'Antonio: Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints an Two Angles

- Flemish painter: The tower of Babel

- Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple

- Garofalo: Christ and the Adulteress

- Sebastian Vrancx: Elegant Company Dining Outdoors

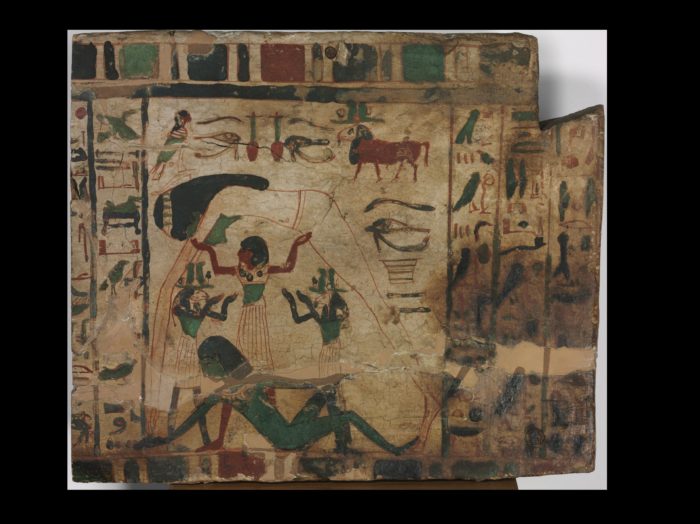

Fragment of a coffin

Let’s go back to the beginning and take a look at this Egyptian coffin fragment from the tenth century BC.

This fragment depicts the separation of the sky from the earth, which forms part of the creation myth in Heliopolis. Here we can see Shu, the son of the first creator god, Atum-Re, as he is lifting the sky – who is his daughter, the goddess Nut – above his head. Lying underneath them is Nut’s brother Geb, god of the earth. Hence the earth became the realm of plants, animals and people, while the sky – the “celestial Nile” – held up by the god was sailed through every day by the solar barque from east to west.

Although at first sight this fragment might appear to be a naive and simple depiction, paintings in ancient Egypt followed strict rules. The details of every object and living being had to be shown from their most characteristic angle (based on their largest surface). Observe the figures of Shu and Geb: their legs are depicted from the side, their hips in a three-quarter profile, their arms and faces again from the side, while their eyes, shoulders and trunks are shown from the front. The use of colours was also determined by rules (the skin of men had to be brownish red, and that of women light brown and pink), and later, in the New Kingdom, even the size of a figure was regulated: its scale depended on its importance. Egyptians did not depict what they saw – did not paint after life – but painted what they knew. They took little interest in the realistic representation of space and depth of space, the latter of which was often suggested by overlapping forms covering each other. They divided space into planes and since their ambition was not to capture what they saw, the problem of perspectival depiction was non-existent at this time.

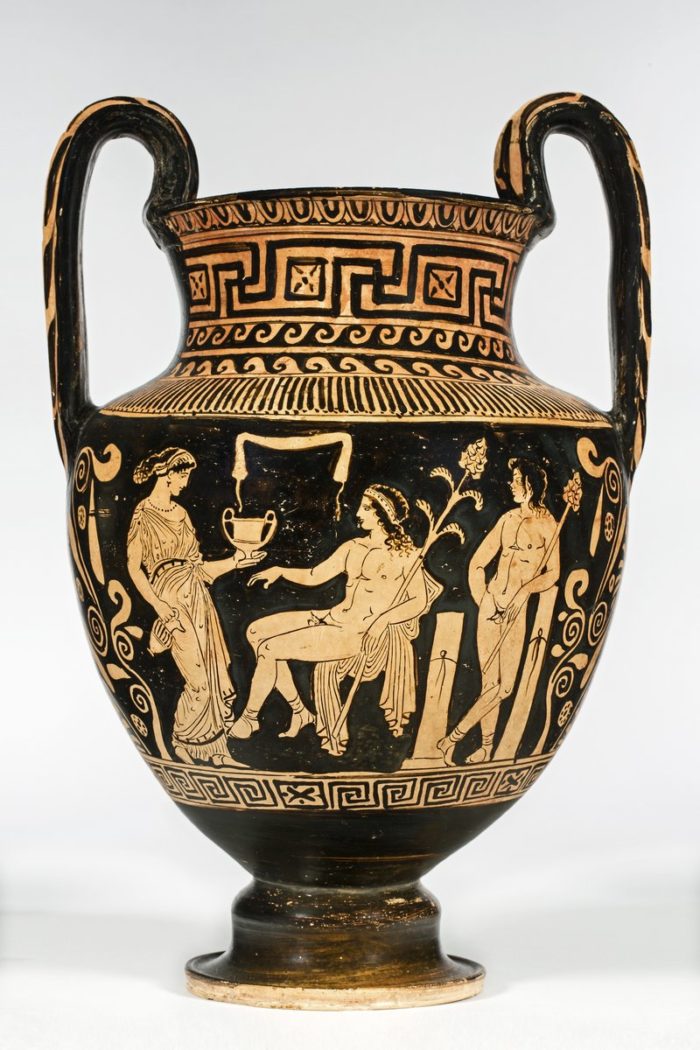

Lucanian red-figure nestoris

In antiquity, we can already observe foreshortening in the depiction of some objects, and the wall paintings in Pompeii also show some attempts at perspective.

In the scene on this red-figure vase, the posture of the bodies and the position of the body parts relative to each other indicate depth of space. Despite the homogenous black background, space has perceptible depth here.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the Byzantines turned away from these achievements and returned to divine symbols and order.

Long centuries had to pass for linear or central perspective to appear in paintings. So what was the reason for this? There simply was no need for it. With the spread of Christianity, the central theme of art was faith and its mediation to the faithful. Capturing this did not require the depiction of physical space surrounding people but rather that of the world beyond it – be it heaven or hell – and, above all, conveying God’s glory. This could be best achieved by the use of a golden background and not with mountains and hillocks disappearing into the distance. The parallel lines did not meet in a vanishing point in the depth of the paintings but “before” the picture plane, thus pulling the viewers into the space of the composition and allowing them to partake in divine acts and miracles.

The influence of Byzantine art continued to be powerful in Italian painting even in the thirteenth century, which can be seen in this picture from Siena.

Try and find those elements of this painting that indicate the depth of space, although not as emphatically as can be seen a century later. The arch on the wooden panel and the bands placed behind each other at the bottom add a certain depth to the picture and so does the cross with Christ’s figure in the foreground. However, we cannot talk about real perspective here but only about picture planes placed above and behind each other.

Guido di Domenico di Tantuccio: Account book cover for the Biccherna office of the city of Siena (currently not on display)

This account book cover – obviously the work of a minor artist – is also from Siena. Although the aspiration for perspectival representation is emphatically present here, there are some mistakes in the implementation. Take a look at the receding lines of the parapet and the table as well as the grid on the window, in which the lines run the wrong way. Apart from these minor blunders, it is noteworthy that the artist made a great effort to accurately represent space, even though it is not a very significant work like an altarpiece would be. Here the artist did not use symbols but rather strove to depict a scene from everyday life with the tools of painting, among which perspective plays an important role.

Maso di Banco: The Coronation of the Virgin

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries there was a revival of interest in Rome. As a result of the fine arts of ancient Rome, attention was turned again to the depiction of reality. By then, artists had known many of the rules of linear perspective but still lacked the mathematical knowledge to lend logic and consistency to perspectival representation. Italian artists combined the observation of nature with simple measurements, mainly thanks to Giotto.

Maso di Banco’s painting (earlier attributed to Giotto) is still pervaded by the divine hierarchy typical of Byzantine art but there is a clearly observable ambition to represent reality. We can virtually feel the weight of the robust figures, while the painter strove to follow the rules of perspective in the depiction of the throne.

The “invention” of perspective is linked to two Florentines: Filippo Brunelleschi (sculptor and architect) and Leon Battista Alberti (architect, artist and theoretician). It was probably Alberti who created the geometrical system that serves as the basis for perspectival representation.

Petrus Christus: Virgin and Child under an Arch

While in Italy the observation of nature was coupled with measurements to produce commanding works of art, artists in Northern Europe focused on the ability of the eye.

They studied colours and light extensively, which was an essential prerequisite for discovering the rules of aerial perspective, a method creating the illusion of depth through the use of colours, where the colour of objects closer to the viewer is more saturated, while more distant objects are more faded and blurred and have a bluish-greyish tone.

The Italian system of perspective is combined with the northern aerial perspective primarily based on observation in Petrus Christus’s Virgin and Child under an Arch, which is one of the first northern paintings where the artist used an accurate linear perspective. If you extend the lines of the flooring in your mind’s eye, they will meet in a single point: the orb held by the child Jesus. The landscape background with its bluish tones further enhances the illusion of depth in the composition.

Andrea del Verrocchio (workshop of) Biagio d'Antonio: Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints an Two Angles

Another depiction with a vanishing point is this altarpiece painted in Verocchio’s workshop for the church of the Dominican order of nuns in Florence. You can see the characteristic features of Florentine Early Renaissance: antiquising carvings on the throne and the parapet, as well as a foreshortened marble floor. You can find the vanishing point here too by extending the lines of the floor: they meet in the Virgin Mary’s crown.

Flemish painter: The tower of Babel

This Flemish master, his identity clad in mystery for now, was not confused by the chaos of languages but rather by the rules of perspective and connecting the fantastical building complexes of his own imaginary tower of Babel. Despite the mistakes he made in depicting space, he produced a spectacular, richly detailed and compelling work. His ambition was most likely to emulate Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s paintings but the coordination of this large number of architectural elements obviously got the better of him. In any case, this painting sends us the message that perspective was an unavoidable aspect of depiction in painting at the time. Prominent and minor artists had a predilection to impress viewers with their spectacular squares and architectural complexes.

Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple

This piece of the altar depicting the life of the Virgin Mary still contains a gilded terminal ornament, which was a late Gothic element. The master set the scene in an open church interior: the child Mary (her young age indicated by her tiny size) advances along a long staircase turning at right angles to enter a shrine flanked by two columns. Despite this work originating from around the same time as Verrocchio’s painting, discussed earlier, it appears as if the two were decades or even an entire century apart. The artist clearly strove to use perspective here but the influence of Gothic art is still strong and the emphasis is on the decorative draperies in this picture rather than the accurate depiction of space.

Garofalo: Christ and the Adulteress

Half a century or so earlier, Garofalo from Ferrara, Italy applied the rules of perspective with great confidence. Of course this is not such an intricate architectural complex as the unknown Flemish painter’s tower of Babel. The church interior provides a classical antiquising background for the small multifigural painting titled Christ and the Adulteress. This painting is a typical collection piece with its small size accommodating thirty-five figures composed into a group, and thus evocative of Raphael’s The School of Athens or his fresco Disputa decorating the wall of the Stanza della Segnatura.

The vanishing point of this painting is the “secret” behind an open curtain behind the central figure, Christ.

Sebastian Vrancx: Elegant Company Dining Outdoors

Vrancx, renowned for his battle scenes, painted this scene of a company dining outdoors. Iconographic precedents of this work include the allegorical picture types known as the “Garden of Love” and the “Garden of Delights”. The master’s Italian training is confirmed by the Renaissance architectural elements and the group of comedians, whose clothes evoke the commedia dell’arte artists. Vrancx brilliantly combines the linear and aerial perspectives, melding the achievements of Italian and Netherlandish art in this piece. The lines of the architectural elements and the furniture receding into the distance converge in the gate in the background, while the colours gradually quietened from bright red into blue and grey tones. The strength of this painting, however, is not this but the narrative with many figures, interesting details and simultaneous scenes within one composition.