We use cookies to provide you with the best possible service and a user-friendly website.

Please find our Privacy Policy on data protection and data management here

Please find more information on the cookies here

Journey to the Netherworld – Rebirth in Ancient Egypt

The mysteries of birth and the unavoidable death have captured the human imagination since the dawn of time. To the ancient Egyptians, death was definitely not the end of life but a transitional stage of a journey to the hereafter, a passage from one form of existence to another one. Everything they learned and experienced was apparently part of a cycle: the daily rising and setting of the sun, the waxing and waning of the moon, the movements of the stars across the sky, the annual flooding of the Nile, the sprouting and drying of the plants, all served as evidence for the Egyptians of a life regularly renewed by creative forces. Even their own lives were conceived as a cycle which moved from birth through adulthood and old age to death followed by rebirth.

The ancient Egyptians believed that living according to the divine precepts while on earth and having both the soul and the body properly prepared after death would open the way for a second life in the hereafter, which was free from the trials of worldly existence. Nevertheless, travelling to the realm of Osiris, god of the netherworld, was not a safe and uncomplicated journey. The Egyptians sought to assist the deceased by placing a range of artefacts inside the tomb, which provided their owner physical as well as magical protection during his perilous way to the afterlife.

Stations

- The creator sun god

- Osiris, the resurrected god

- The funerary procession

- Anubis and mummification

- A ritual journey

- Nut, goddess of the sky

- The face of the resurrected

- Soul-bird

The creator sun god

According to the ancient Egyptians, the sun god sets behind the western horizon every evening and sails through the netherworld during the twelve hours of the night. Along the way, his rays illuminate the dead and fill their realm with life. In the morning, the sun god rises again on the eastern horizon, young and rejuvenated, and recreates the world of the living. During his journey, the god takes on multiple forms: at dawn he appears reborn as a scarab, at noon he takes the shape of a falcon, and at sunset he boards the evening barque as a ram-headed man to sail the subterranean waterways.

The Egyptians considered the scarab (Scarabeus sacer) as a symbol of renewal and rebirth. The young beetles were hatched from a ball of dung, and this event was seen as much a mystery as the birth of the sun god: an act of spontaneous self-creation. Representations of a scarab-shaped deity rolling the newborn sun disk above the eastern horizon were modelled on the beetle pushing a ball of dung along the ground with his back legs. The rising sun god himself was frequently depicted as a scarab with outstretched wings, and a necklace with a winged scarab pendant was often placed around the neck of the deceased so that, along with the sun god, he would also be reborn in the afterlife.

To access the object’s data sheet and to zoom the image, click here.

Osiris, the resurrected god

A mythological story relates that the reign of Osiris was one of the most flourishing and peaceful periods in Egypt’s history; prosperity and order prevailed in the country. This Golden Age, however, did not last long. Osiris’s younger brother, Seth, grew jealous of his brother’s power, conspired against Osiris, and eventually murdered him. Seth cut his body into pieces and scattered them across Egypt, hiding the body parts from the gods. Isis, sister-wife of Osiris and goddess of healing and magic, went searching for the pieces of her husband’s body, and she was able to recover them with the aid of her sister, the goddess Nephthys. Isis joined the pieces through her power of magic, and the reassembled body was embalmed and wrapped in strips of linen by the god Anubis. Osiris became the first mummy, and the enactment of proper funerary rites allowed him to resurrect. The story of Osiris’s death and resurrection offered the promise of overcoming death and reversing the decay of the body. It served as a mythological archetype for Egyptian embalming practices: having received the same treatment of the corpse, the deceased could hope to be reborn as a god, endowed with his own personal “Osirian” aspect.

This bronze figurine, dated to the seventh–sixth centuries BC, depicts Osiris standing, enveloped in mummy wrappings. He is shown holding his royal regalia: the hook and the flail. The crown adorned with the uraeus-cobra defines him as a royalty, whereas the two ram’s horns added to either side of the crown symbolize resurrection. Therefore, the statuette represents Osiris as having been raised from the death, acting as the ruler of the netherworld.

To access the object’s data sheet and to zoom the image, click here.

The funerary procession

Once the embalming and wrapping were completed, much in the same way as it had been done to Osiris, the mummy was placed in a coffin. After the night vigil, the corpse was transported from the deceased’s dwelling to the necropolis. The coffin was dragged to the river bank on a sledge drawn by a pair of oxen, followed by the deceased’s relatives and friends, female mourners, priests performing funerary rites as well as dancers and musicians. The funerary procession also included servants carrying the canopic jars that contained the deceased’s removed viscera and all the grave goods that were to be buried with the dead person. The two ladies (usually female relatives or hired mourners), who attended the coffin wailing and chanting laments for the dead, acted the mythical role of the divine sisters, Isis and Nephthys mourning over the corpse of Osiris, thus facilitating the successful regeneration of the deceased in the afterlife in his “Osirian” form.

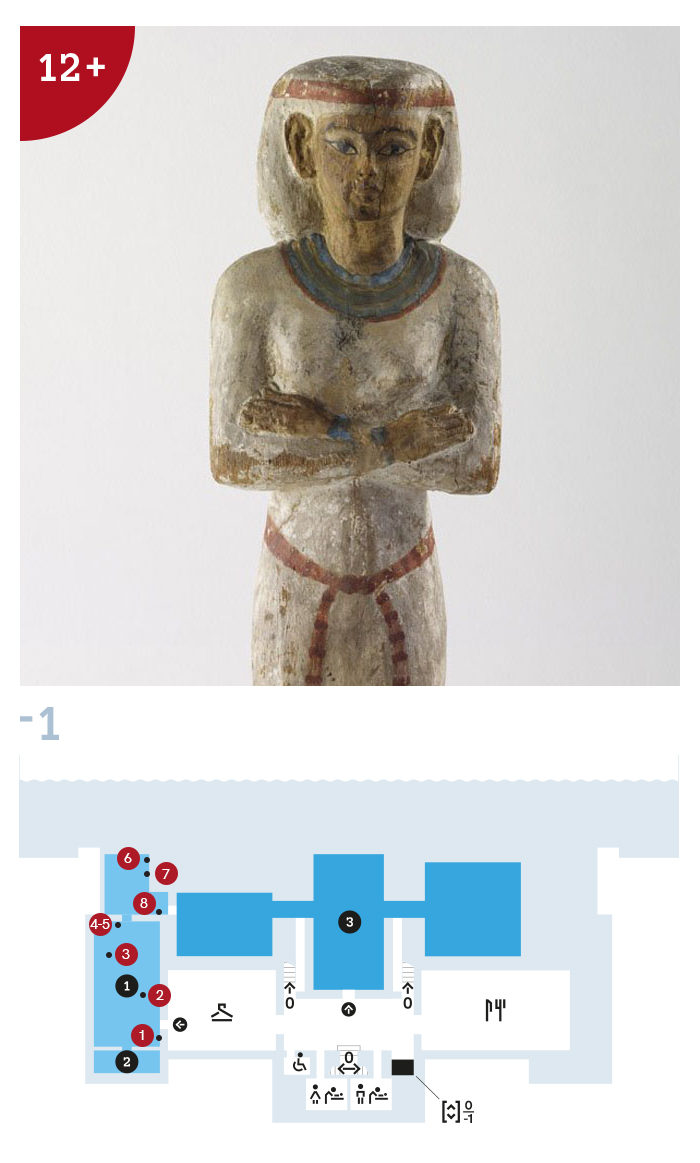

This painted wooden figure depicts a young lady clad in a white linen dress which gently follows the contours of her slender body. Even if the statue bears no inscription at all, she can still be identified as either Isis or Nephthys with great certainty. The piece must have been attached to one end of a ritual funerary barque (or a barque-shaped shrine) used to transfer the coffin and the grave goods across the river from the east (symbolically, the land of the living) to the west bank of the Nile (the cemetery, the realm of the dead). Having arrived at the west bank, the procession continued to the entrance of the tomb.

Anubis and mummification

Egyptians believed that the human personality had many facets; it was a composite being of different entities and maintaining the integrity of a person was an all important prerequisite of life in the hereafter. The physical components, such as the heart and the body, were to be carefully preserved by the proper preparation of the corpse. Mummification, however, was not just about preventing decay; it was a ritual process during which the body was transformed into the deceased’s everlasting effigy.

The second register from below on this fragment of a painted coffin depicts Anubis, the jackal-headed god, leaning over the body of the deceased, which, already preserved and bandaged, is resting on an embalming bed adorned with lions’ heads and feet. The figure of the deity was painted black as the ancient Egyptian associated this colour with the idea of regeneration.

The most detailed account of the various embalming practices has been provided by the Greek historian Herodotus who visited Egypt around 450 BC. He described three different methods based on social class, the most perfect (and the most costly) of which was the one that was also applied to the body of Osiris. First the corpse was washed, the brain and the viscera were removed, and the interior was thoroughly purged and cleansed. The next step involved removing all moisture by covering the eviscerated body in natron. Cavities were filled with linen, pure myrrh, cassia and aromatic resin, and the body was anointed with various kinds of oils, resins, and unguents. Finally, the locks of hair were arranged and the body parts were wrapped in strips of fine linen. Depending on the financial situation of the deceased, several magical amulets and small pieces of jewellery were placed within the bandages and on the mummy shroud during the wrapping process. These were considered as symbols of protection and rebirth. The mummification scene of the coffin fragment depicts four containers under the embalming bed. They are called canopic jars in which the removed and embalmed viscera would be placed. Each jar was reserved for a specific organ: the liver, lungs, stomach, and intestines, and each of them were magically protected by one of the four Sons of Horus as indicated by their removable lids in the shape of the heads of their protective deities (the human-headed Amsety, the jackal-headed Duamutef, the falcon-headed Qebehsenuf, and the baboon-headed Hapy).

To access the object’s data sheet and to zoom the image, click here.

A ritual journey

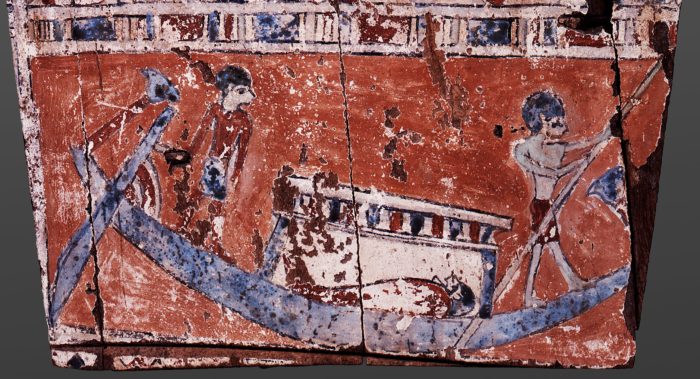

The bottom register of the coffin fragment depicts a barque bearing the mummy in his coffin beneath a canopy, with a crew of an oarsman in the prow and a helmsman at the stern. The scene was clearly intended to evoke a ritual journey: either the transportation of the coffin across the river to the cemetery on the west bank of the Nile, or the deceased’s last (most often allegorical) pilgrimage to a sacred place like Abydos, the holy city of Osiris. The boat resembles the barque of the sun which is a further allusion to the fact that the deceased’s journey to the tomb was seen as a symbolic imitation of the sailing of the sun god on a cosmological plane. Such a correspondence would guarantee the individual’s rebirth as a divine entity and his successful transition to the afterlife.

Nut, goddess of the sky

Nut is considered one of the oldest deities of the Egyptian pantheon, a personification of the sky and the vaults of heaven. She appears in the creation myth of Heliopolis as the granddaughter of the creator god Atum, and had four children: Osiris, Seth, Isis and Nephthys. The sun was believed to be swallowed by Nut at sunset, only to be reborn from her womb next morning.

The idea that the coffin lid was identified with Nut whereas the base with earth god Geb, goes back to very ancient times. The coffin represented the universe, enclosing the deceased identified with Osiris or the sun god Ra who, according to the order of the cosmos, was reborn from Nut’s body. The underside of coffin lids was often painted with the figure of the goddess, but she may also appear quite frequently on the outside. In that case Nut is depicted kneeling with arms and wings outstretched protectively over the chest of the mummy.

Not only coffins but mummy trappings, fashioned from cartonnage and placed directly over the embalmed body, could have been decorated with the protective image of the sky goddess. Cartonnage is a type of material made of several layers of linen or papyrus, stuck together, and covered with plaster. The object shown here once belonged to a set of mummy trappings adorned with the most important symbols of regeneration. Quite unusually, the arms and legs of Nut were painted green in this piece.

To access the object’s data sheet and to zoom the image, click here.

The face of the resurrected

A funerary mask fastened over the mummy’s head had two basic functions. On the one hand, it served to restore the senses of the deceased so that he could see, hear, smell and taste again; on the other hand, it was also expected to defend the face from hostile, malevolent supernatural forces. Such a mask was not intended the preserve the true likeness of an individual in the sense of a portrait; rather, it provides an idealized image of the deceased as an immortal, resurrected being in the next world.

Since the glorified dead were believed to be reborn in the realm of Osiris as gods, their appearance reflected their divine character: their bones turned into silver, their hair into lapis lazuli, and their flesh into gold. This idea is beautifully illustrated by the colour scheme applied to the mask: a dark blue wig, imitating the locks of lapis lazuli, frames a gilded face recalling the golden flesh of the gods. The cartonnage mask shown here was made for the burial of a child and dates to the first century BC.

For a 3D image of the mummy mask, click here.

Soul-bird

The Egyptians believed that upon death, the unity and cooperation of physical and spiritual components making up a person was dissolved; the body began to decay and the soul left the corpse. Of the immaterial constituents, the ba is sometimes referred to as a concept closest to the contemporary Western religious notion of the “soul”, and it was often depicted in ancient pictorial representations as a human-headed bird. The bird-form was meant to express the mobility of the soul after death. By day, the ba could leave the grave, go on excursions in the world of the living, or simply perch on a nearby tree, but it had to return to the tomb for the night. Immortality in the afterlife, however, could only be achieved through the post-mortem unification of the body and the ba with another non-corporeal element of crucial importance: the ka. The ka came into existence at the moment of one’s birth, and it was often represented as a spiritual double or a second image of the person. Since it was essentially non-physical in character, the ka needed a preserved body (the mummy or a funerary statue in the likeness of the deceased) to inhabit.

This wooden ba-bird statuette was produced some time between the sixth and the second centuries BC, and originally it may have been attached to a piece of funerary furniture, a shrine, a stela or a coffin.