We use cookies to provide you with the best possible service and a user-friendly website.

Please find our Privacy Policy on data protection and data management here

Please find more information on the cookies here

From false beards to hipster beards

Taking a walk in Budapest’s city centre or looking around in a ruin pub, one encounters more beards than clean-shaven faces. This is the trend for men right now but some fashion bloggers assert that sporting a beard has already had its heyday and a freshly shaven face will again become the norm. What do we know about beards? Do they mean something? What does having a beard say about its wearer? Is it a fashion or tradition? According to Giovanni Scaliger, a 16th-century humanist, the beard is “the most important and most sacred part of a man.” Is that really true? Let’s see.

Stations

- Head of a Man

- Portrait of Hermarchos

- Portrait of a Greek Philosopher (so-called Pittakos)

- Portrait of Euripides

- Giovanni Santi: Vir Dolorum

- Andrea del Verrocchio: Vir Dolorum

- Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano: The Penitent Saint Jerome in the Wilderness

- Jacopo Bassano: Portrait of a Cardinal

- Titian: Portrait of Marcantonio Trevisan, Doge of Venice

- Giovanni Battista Moroni: Portrait of Jacopo Foscarini (?)

- Paolo Veronese: Portrait of a Man

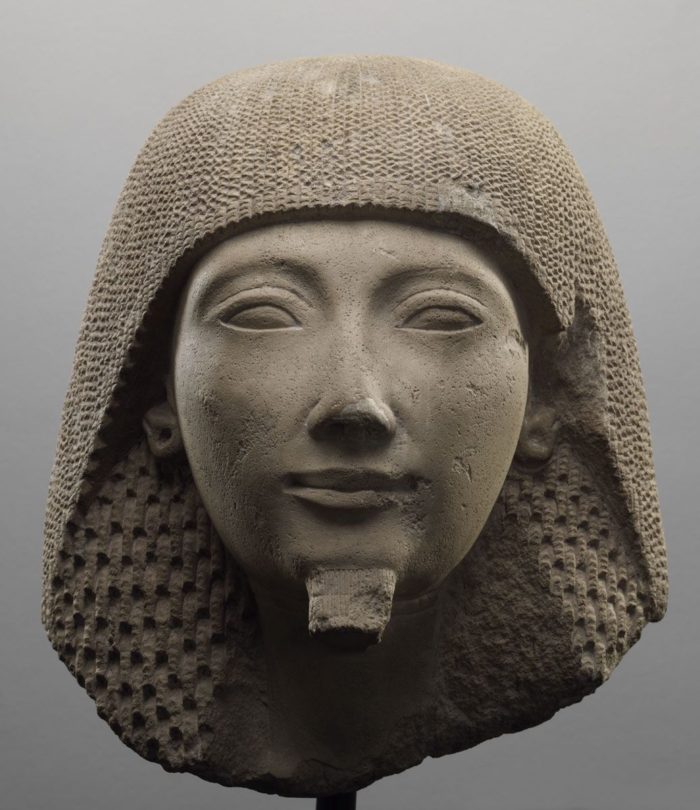

Head of a Man

Since the facial hair of Egyptian men was quite sparse, the wearing of a false beard, which had a ritual meaning, was the prerogative of the pharaohs, and as such, female rulers also had to wear one as a sign of their divine origin…

The portrait of this young man is one of the jewels of the Museum of Fine Arts’ Egyptian collection. He is wearing a meticulously fashioned, double wig that cascades down in steps; his high rank is indicated by the false beard on his chin, behind which the ancient sculptor had left the stud supporting the area around his Adam’s apple. In accordance with the traditional rules of depiction during the period, the face is idealised and ageless. This brings us no closer to the man’s personality and his features betray nothing of his feelings. This all invests the portrait with a mysterious, incomprehensible beauty. The head once formed part of a sitting or kneeling statue, while the titles and name of the owner are engraved in the back pillar, but only a few symbols of the hieroglyphic inscription have remained. For the Semitic peoples, the Assyrians and the Babylonians, the wearing of a beard was a religious observation. In Mesopotamia, the length of facial hair showed a man’s position in society: those with greater authority had longer beards, while a shorter one designated a more humble societal rank. To their shame, slaves had to live with a clean-shaven chin.

Assyrian men arranged their beards into curls, and according to descriptions in the Bible, Jews allowed their facial hair to grow. Nowadays, Orthodox Jews still observe this rule, and so do Rastafarians.

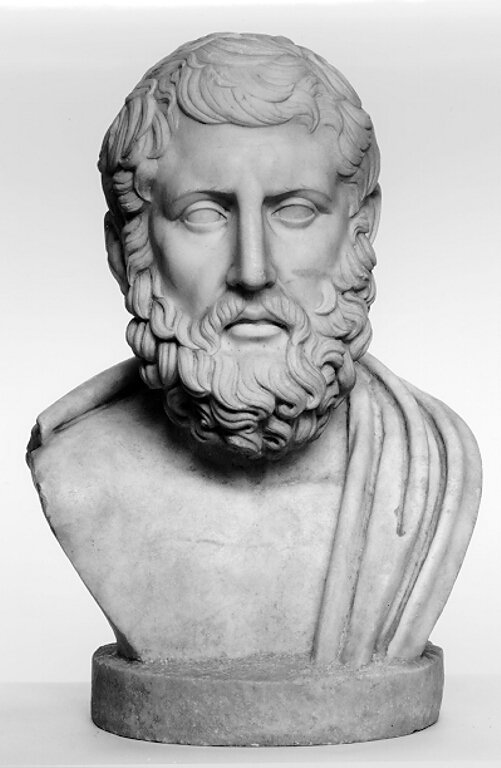

Portrait of Hermarchos

The ancient Greeks and Romans also grew beards. They devoted a great deal of care to their appearance, and grooming their hair, beards and moustaches was part of everyday life for men in the ancient world. According to the surviving portraits, philosophers and thinkers in the older age group generally wore beards. This portrait was identified on the basis of an inscription on a bronze work from Herculaneum: it depicts Hermarchus, a student of Epicurus. After Epicurus’ death, his student took over his master’s school in Athens; in his writings he challenged the teachings of Plato and Aristotle.

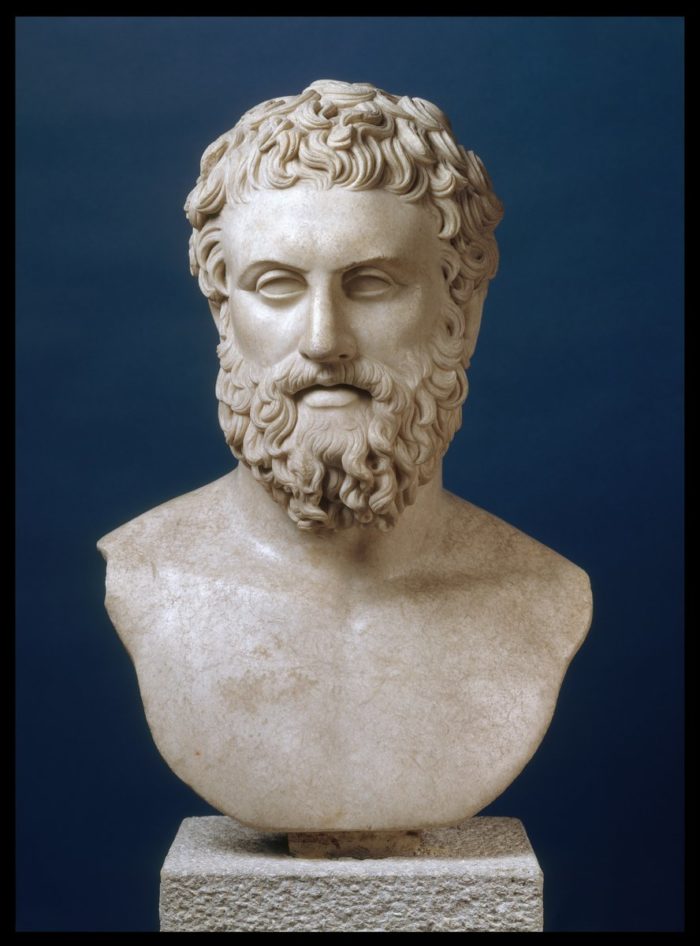

Portrait of a Greek Philosopher (so-called Pittakos)

Mention of the Seven Sages of ancient Greece can be found in various records, although there are only four permanent members (a total of 21 names can be compiled from various sources), including Pittacus. This portrait may be a depiction of him, showing him with a moustache and a beard, like those generally worn by philosophers and sages at the time. The Seven Sages had another distinguishing feature: a laconic style of speaking, such as these gems from Pittacus: “A half is more than the whole”, “Land is certain, the sea is uncertain”, “It is difficult to be good.”

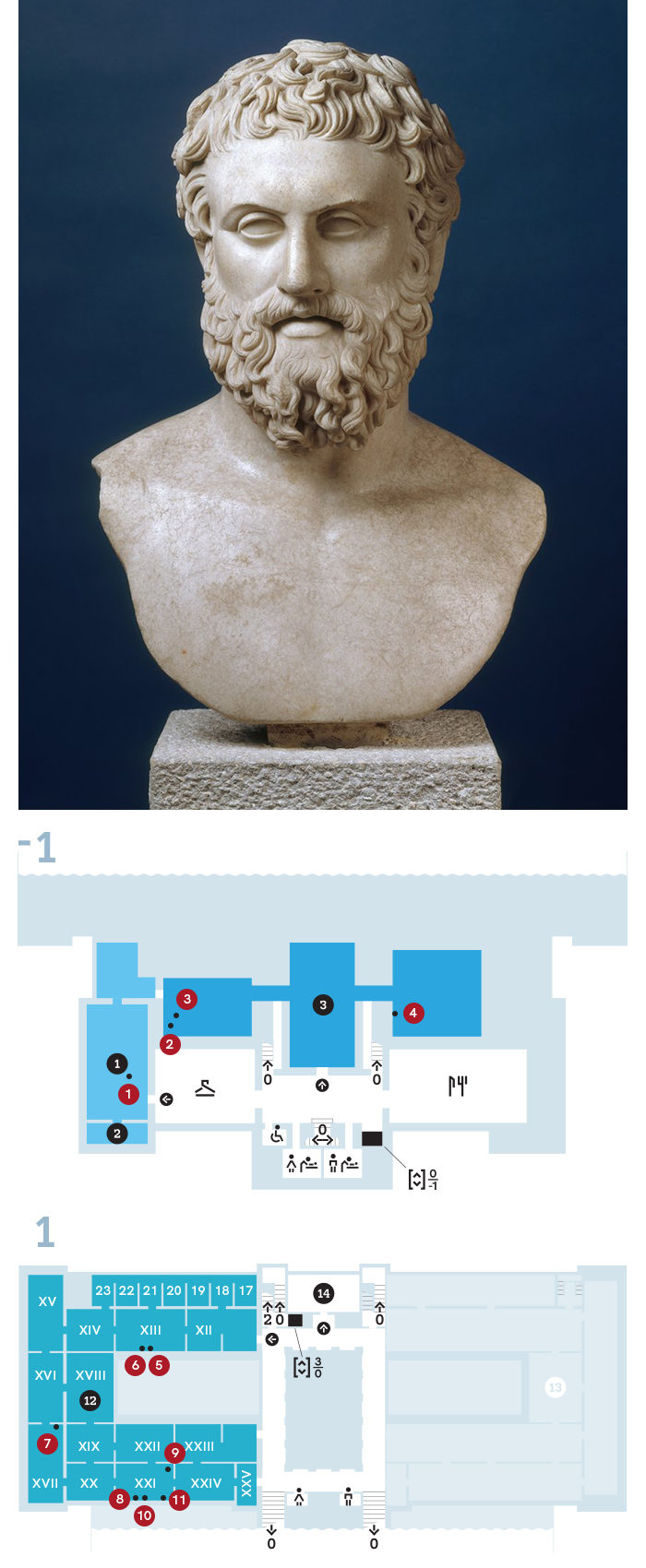

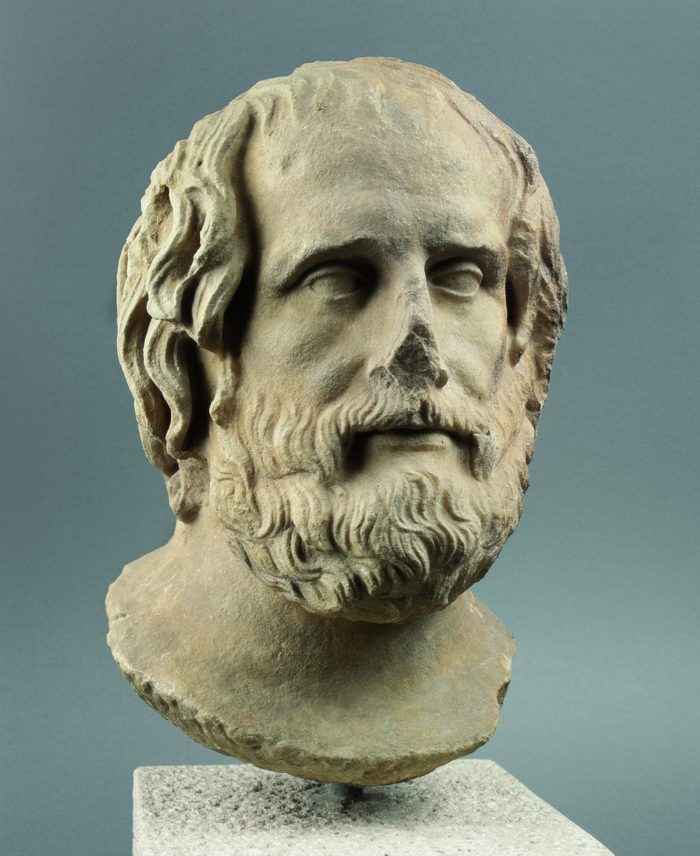

Portrait of Euripides

This Roman copy was made after the Greek portrait depicting the Greek tragedian, Euripides. According to some scholars, the original work may have been made by Lysippos. Whoever the sculptor was, his genius is shown by the fact that he did not merely create an idealised portrait but tried to capture the individual features of his model. Euripides’ popularity continued into the Roman period, so numerous replicas were made after the Greek originals. Similarly to the ancient thinkers, the famous dramatist also wore a beard with his hair in somewhat dishevelled locks. At the same time, shaven, smooth faces also became widespread in countries conquered by Hellenism. Alexander the Great did not wear a beard – and indeed he expected his soldiers to have a shave before battles, lest the enemy grab hold of their beards. Those who came in the conqueror’s wake thought it prudent to adopt this tradition too, and thus the smooth little boy-like face became widespread in the Hellenic world. In Egypt, the smooth, shaven face persisted independently of Hellenic conquest, while in Persia the curly, well-groomed facial hair true to earlier traditions persisted as the generally accepted style. Roman emperors and nobility were the first to be depicted on reliefs and in statues with shaven faces. However, fashion constantly changes, which was also the case in the 1st and 2nd centuries, just like in modern times. The emperor Hadrian brought beards back into fashion and they remained popular for centuries on the European continent. At this point, let’s see the origin of the Latin name of the beard: barba. It can be traced back to the Celtic word, barb, which means man, and can also be linked to the term barbarian.

Giovanni Santi: Vir Dolorum

In the Anglo-Saxon territories men had worn beards until Christianity gained ground and the rules pertaining to the clergy were slowly adopted in secular life. English dukes wore beards until 1066, when, thanks to an act passed by William the Conqueror, they had to shave them off, in order to fit in with the norms of fashion at the time. In the 12th century, Pope Alexander III snipped his way into the beard’s centuries-long tradition on the Continent by prescribing that the priesthood be clean-shaven. Of course there were and there are those who think that rules are made to be broken. This attitude can be seen in the second half of the 20th century, when wearing a beard became a characteristic feature of revolutionaries and rebels (hippies and hipsters). The most well-known bearded man is with no doubt Jesus, who with the way he wore his hair and his beard found not only followers in his own time but for centuries after, right until our own times. Giovanni Santi, Raphael’s father, depicted Vir Dolorum, or Man of Sorrows, here: i.e. Christ in his living and dead states, the Holy Sacrament embodied. The purpose of the painting was not only to encourage the elevation of the faithful but also to display artistic virtuosity. The fly painted next to Christ’s chest is a symbol of death and sin, while Santi also used it to create an illusion: it is a motif of Netherlandish origin, a magical talisman to ward off real flies. Let’s not forget about Christ’s beard, which, similarly to his hair, is parted in the middle and combed to one side. Perhaps it followed the fashion of the time; in any case, it closely resembles the hair style and beard of the Man of Sorrows statue you can see right next to this painting.

Andrea del Verrocchio: Vir Dolorum

Although from the 13th century onwards, wearing a beard was banned by church law, between 1527 and 1700 popes wore beards. Pope Clement VII grew a beard as a sign of his mourning after the Sack of Rome, and his successors carried on this custom for some peculiar reason up until the rule of Pope Innocent XII.

Those members of the clergy who vouched for the beard, probably looked to the example of Jesus, who is always shown with a beard, except for the Good Shepherd depictions.

This terracotta sculpture evokes Giovanni Santi’s Vir Dolorum, but while the face of Christ exudes serenity and acceptance in the painting, the sorrow of mankind is virtually made palpable in the sculpture.

Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano: The Penitent Saint Jerome in the Wilderness

Saint Jeremiah must have had a long beard as depicted here – or something like this –because of his ascetic lifestyle. Having joined a group of ascetics, he spent five years in the desert of Chalcis, near Aleppo, living as a hermit, where a clean soul took precedence over a clean-shaved face. Jeremiah was more than an ascetic: he was a Bible translator, anointed priest and a bishop too, which the books placed on the rocks in this picture allude to. In this composition, the landscape that surrounds Jeremiah seems to take the main role, and as such, this depiction can be regarded as an early example of landscape painting which would soon become a genre of its own. The various landscape elements – mountains, wilderness, rivers, seas, plough land, villages, castles and animals – proclaim the glory of Creation.

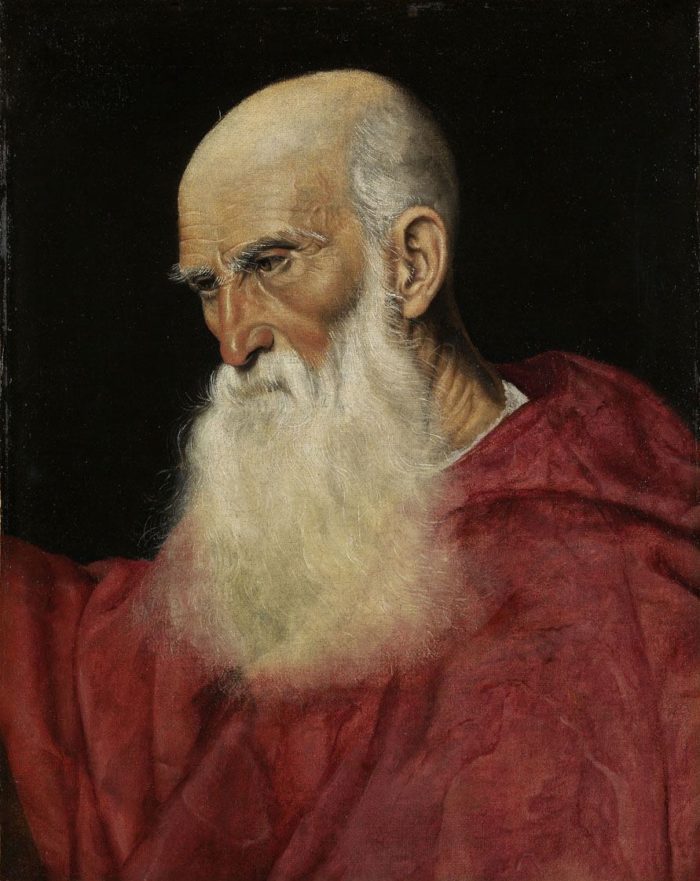

Jacopo Bassano: Portrait of a Cardinal

This painting was made after the Sack of Rome, when clerics – especially high-ranking ones – no longer insisted on a clean shaven face. The portrait had previously been thought to depict Saint Jeremiah because of the ascetic, introspective countenance and the red chasuble. However, the individual features suggest that it might have been painted of a specific person, perhaps bishop Pietro Bembo. It is likely that the bishop regarded Jeremiah, who also bore the title of bishop, as a role model and wearing this kind of beard was a sign of his tribute for the saint.

The regulation of popes wearing beards was surrounded by ardent controversy even in the 16th century, and beard fashion in secular Europe also changed from century to century.

Titian: Portrait of Marcantonio Trevisan, Doge of Venice

The doges, i.e. chief magistrates of Venice, had a preference for beards. As attested to by the portraits of the time, the mid-length, well-groomed and trimmed styles were the most common.

Titian’s expressive, virtuoso painting makes palpable not only the shiny brocade robe of the sitter but also his grey beard. Interestingly, this portrait made of the doge, who held office for only one year, was consumed by fire and Titian himself made a new copy or version of it.

Many men opted for wearing a beard throughout Italian history, including generals, magistrates and clerics. This symbol of masculinity is worn by the majority of the men depicted in the Renaissance portraits found in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts.

Giovanni Battista Moroni: Portrait of Jacopo Foscarini (?)

Moroni was among the foremost portraitists in 16th-century Italy. As tradition has it, Titian referred clients who he was unable to take on to Moroni. According to the inscription, the portrait depicts Jacopo Contarini, the podesta (chief magistrate) of Padua; however, records prove that Padua did not have a podesta by that name and in that year the office was held by Jacopo Foscarini.

Paolo Veronese: Portrait of a Man

The portrait of this young man clad in a splendid robe lined with lynx fur not only reflects the sumptuous fashion of the period but also showcases the virtuosity of Veronese’s painting technique. The subtle details, the glossy gloves, the short haircut and the beard provide an authentic picture of the fashion of the day, since the noble youth with a look of openness and trustworthiness obviously paid attention to his appearance and observed the trend of his time.

In 1535 King Henry VIII (1509-1547) – who had a beard himself – decided that men who grow facial hair were obliged to pay tax and introduced the beard tax: of course in proportion to the beard-wearer’s social standing, since having a beard was a status symbol in those days. After his death, the beard tax was not collected for some years, but during the reign of Elisabeth I it was reintroduced, and this time with more severe conditions: every man (regardless of being a nobleman or a serf) whose face was not touched by a razor for two weeks had to pay. Laws and regulations here or there, the fashion of beard-wearing kept conquering Europe over and over again. This can perhaps be explained by the fact that for decades and centuries on end, the beard never failed to be seen as one of the symbols of masculinity and the assertion of manly confidence along with its other, previously mentioned meanings. The beard styles constantly changed and are changing still, giving free reign to barbers’ creativity. However, there is a particular type of beard that has been in fashion since the 16th century and actually owes its popularity to a Dutch painter. In many of Anthonis van Dyck’s portraits of men, you can see a short, pointed beard, which was the most fashionable style of beard at the time, favoured by the painter himself. Based on the portraits, it has been called the Van Dyke/Van Dyck beard to this day.