We use cookies to provide you with the best possible service and a user-friendly website.

Please find our Privacy Policy on data protection and data management here

Please find more information on the cookies here

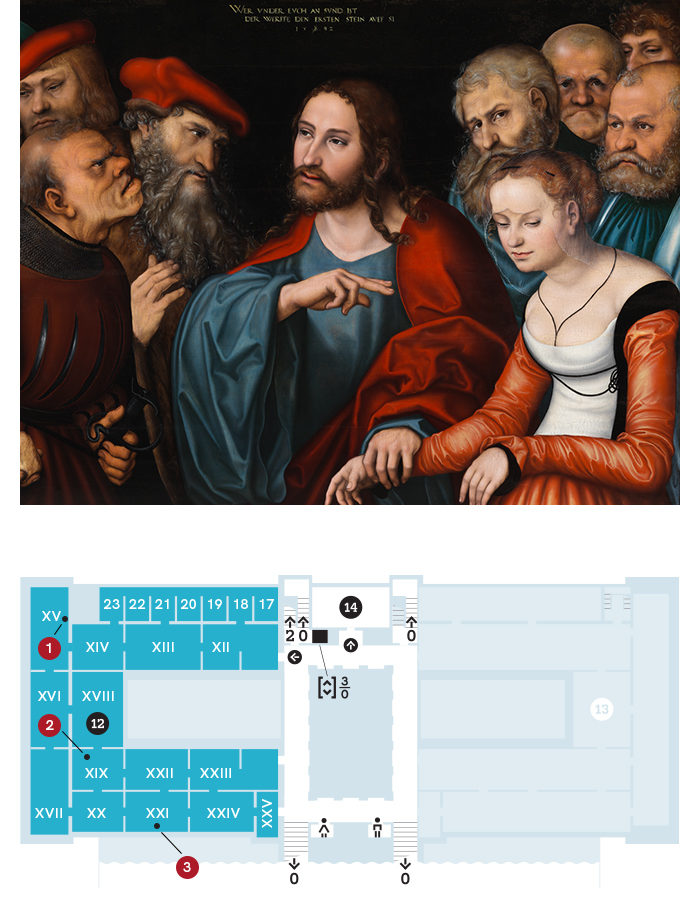

Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery

The story of Christ and the woman taken in adultery occurs in only one of the four gospels, John, 8. For centuries this event was very rarely depicted until, around 1500, it became a frequent subject for painting and for graphic art, mostly in Germany and Venice. It was popular in the country of the Reformation presumably because Luther liked to refer to the scriptural story that proclaimed forgiving love instead of inhumanity hiding behind legality. Most of the artistic presentation of this theme originated in Venice. The reason for this, in addition to the German influence, might be that nowhere in Italy was non-dogmatic thinking so deeply rooted as in the cosmopolitan city-state of merchant patricians.

Let us take Vilmos Tátrai’s book as our guide to learn more about the three depictions of the subject in the Old Master’s Gallery.

Stations

- Lucas Cranach the Elder: Christ and Woman Taken in Adultery

- Garofalo: Christ and the Adulteress

- Polidoro da Lanciano: Christ and the Adulteress

Lucas Cranach the Elder: Christ and Woman Taken in Adultery

In the painting Lucas Cranach the Elder, the proverbial words appear on an inscription, „He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.” Below the inscription is the date, 1532, not just the date of the picture but an admonition that the teaching of Christ was valid in the present and so were the costumes of Cranach’s time. The structure of the scene is compact and highly abstract. If I may be permitted a major anachronism, the close-up, half-figure presentation is more suitable to the movies than to the stage. The setting has no significance so far as the subject is concerned and we see nothing of it. There is space only around the head of Christ, the other actors are crowded into two groups bilaterally. The marauder, wearing a slashed gown over armor, hold a rock in one hand and rest his other hand on the hilt of his sword. With his stupid, bestial face he is the embodiment of raw brutality, more the instrument of evil than its intellectual author. The Pharisees and scribes are more dangerous than he. One is avidly waiting to catch Jesus in a law-breaking pronouncement, the other whose evilness is manifest on his face turn to his comrade, seen in profile, with a malignant look. Of the face appearing between them we can see only an eye. This eye, threateningly directed toward us, is a motif of horror and a major triumph for Cranach. On the side of the woman taken in adultery the ones taking Christ’s teaching to heart are tightly grouped. The man closest to Jesus turn toward us friendly sternness, as though reminding us of the last few word of the injunction, “Go and sin no more.” Behind him the fat, bald, toothless old man looks directly at us. His caricature of a face indicates to us that Chranach did not equate ugliness with Evil.

Garofalo: Christ and the Adulteress

There is a spontaneously natural feeling in the gesture that we completely lack in the picture by Garofalo, whom his contemporaries called “the Raphael of Ferrara”. This may also be due to the fact that Cranach stages the event in the vernacular of the people and staffs it with his contemporaries while the Italian Master stages it in the language of Cicero alla Romana. The scene is a pillared hall above a staircase covered by a coffered barrel vault. The clothes are Roman, or at least try very hard to appear so. The play itself is nobly classicizing, and measuredly festive. We don’t have to wonder for long why this picture seems so suspiciously familiar. Garofalo composed a miniaturized version on some of leading motifs of the School of Athens. Whoever delights in variety has no cause for complaint. In this picture there are young and old, attractive and ugly, enthusiastic youth and stern soldier, evil Pharisee and benevolent apostle. Ever since Leonardo’s Last Supper made it so evident, it is accept truth that Christ’s words deeply affected the multitudes. The restlessness increases toward the back and culminates in the figures climbing up the columns. As I have already mentioned, in contrast with Garofalo, Cranach was completely indifferent to the well known fact that the gospel story took place in one of the provinces of the former Roman Empire. Yet the relationship between the artist and the subject is much closer in his work and he grasped more of what we might call, for lack of better term, the eternally human. While Garofalo tries to be faithful to the period of the event, he not only separates the viewer from the action in time but estranges him from the human content of the scene as well.

Polidoro da Lanciano: Christ and the Adulteress

The motifs reminiscent of the period of the Roman Empire are not lacking in the picture by Polidoro da Lanciano, a pupil if Titian’s. The foreground is separated from the background, on the right by a fragment of the Colosseum arches. The soldier on the right wears a chased suit of armor. Between him and the man in the turban, there is a familiar face looking directly at us. We know it from its presence on the marble bust of the Emperor Vitellius. All these details were entered into the painting without pedantry, boasting or artificiality, because of their pictorial rather than historical importance. The painter understood Titian’s message. He could give the scene loftiness without endangering our emotional identification with the depicted event. His theatre is friendly and brings the actors and spectators close to each other and thus even the appearance of the patrons, two Venetian patricians, does not appear strange. The old man with the white beard, wearing the striped cloak, has a more important role than the two Pharisees demanding an accounting from Christ. In bringing Christ’s word to the attention of the adulterous woman with his gesture, he immediately becomes a figure embodying the continuity between the Old and New Testament and the common roots of the Christian and Jewish faiths. Christ need not take the central axis as in the Garofalo, to stand out among his environment. It is sufficient to see the light flare on his red tunic and blue coat and to see on his face that he listens only to an inner voice to the exclusion of everything else.